The cause of delirium in the last days of life is usually multifactorial, involving multiple organ failure and other factors that are now largely irreversible, e.g. hypoxia, metabolic abnormalities.*4–6 However, some causes or exacerbating factors of delirium can be managed in the final days, such as pain, urinary retention, certain medicines (e.g. opioids, benzodiazepines, anticholinergics) or substances (e.g. nicotine withdrawal) and infection (see: “Managing symptoms of delirium”).7–9 People with pre-existing cognitive impairment are at the greatest risk of delirium.7 Other risk factors include increasing age, immobility and vision or hearing impairment.4, 10

Delirium can cause significant distress to the patient and to those supporting them in their last days of life, particularly as this is a time when the patient's cognition, awareness and ability to communicate is highly valued.4, 5, 11 Provide information and support to the family/whānau, including the likely causes of delirium, potential symptoms and address any questions or concerns they may have.4, 12 Reassure patients and their family/whānau that this is a normal part of the dying process.

*Delirium that occurs during palliative care prior to the last days of life can often be reversed if this is in line with the person's goals of care, e.g. by correcting metabolic abnormalities, such as hypercalcaemia, hyper/hypoglycaemia and dehydration

Assessment of delirium

A clinical diagnosis of delirium can be made based on symptom history, pattern recognition and any other relevant information from the family/whānau or carers.1, 4 Validated tools are available to help assess patients for delirium, e.g. Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), 4AT.1, 4 However, these are often not practical or possible to apply in the last days of life, particularly for those with limited communication or fluctuating levels of consciousness.1, 4, 13

As a general approach, ask the patient (if possible) or their family/whānau about features of delirium, including any:1, 4

- Acute change in mental status and whether this fluctuates throughout the day

- Increase in distractions, disorientation, disorganised thinking or other cognitive changes, e.g. hallucinations, aggression

- Changes in consciousness or activity, e.g. lethargy, stupor, hypervigilance, difficulty sleeping

Repetitive plucking of bed sheets or clothing, groaning and facial grimacing can be signs of delirium in the last days of life.4, 5, 14 Some patients may also experience auditory or visual hallucinations, which can be distressing for them and their family/whānau.2, 14, 15 However, these should be distinguished from the positive spiritual visions and experiences that can occur at end of life which are generally comforting and reassuring to patients, and do not require medical intervention.

When deciding on an appropriate treatment plan, consider the patient’s emotional, spiritual, social and physical needs.

First consider any reversible causes or exacerbators of delirium, which can be treated.8, 9, 13 These may include:

- Pain – ensure adequate pain relief.9, 13 For further information, see: “Managing pain in the last days of life”.

- Constipation/faecal impaction or urinary retention – consider use of laxatives/an enema (if possible) or urinary catheterisation if not already in place14, 16

- Medicines, e.g. corticosteroids, anticholinergics, opioids, benzodiazepines – consider discontinuation or if the medicine is required, lower doses or switching to an alternative medicine11, 13

- Other substances. If the patient's symptoms are likely caused by nicotine withdrawal, consider use of nicotine replacement patches.6 A benzodiazepine is often useful for patients with alcohol withdrawal.17

- Infection (e.g. urinary or respiratory tract infection) – antibiotics may improve the symptoms of delirium if treatment is considered appropriate4, 10

- Psychological causes, e.g. fear, anxiety or spiritual distress – use non-pharmacological management strategies, considering what interventions (if any) have helped them to overcome this in the past.7, 13 Antidepressants should not be introduced as there is insufficient time for them to have an effect.18 For further information on the management of psychological symptoms, see: “Support the patient’s mental health and wellbeing needs”.

Prioritise non-pharmacological interventions

Evidence suggests that non-pharmacological interventions are preferable to pharmacological treatments in patients experiencing mild symptoms of delirium.19, 20 Ideally, non-pharmacological management strategies will have been discussed with the patient and their family/whānau prior to the last days of life so that a plan is already in place (i.e. advance care planning, see: www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-work/advance-care-planning/).

Examples of non-pharmacological interventions for delirium:4, 6, 7, 15

- Implement safety measures, e.g. lower the bed, use a floor sensor mat, remove nearby potentially hazardous objects

- Regularly reposition the patient

- Gentle mouth care, if tolerated

- Close observation (e.g. by a volunteer “sitter” or family/whānau). Having someone always present can help with re-orientation and reduce the patient’s fear/anxiety and feeling of isolation.3

- Set an ambient room temperature and consider the patient's proximity to heaters or cold draughts

- Ensure adequate lighting, avoid glare from artificial light or sunlight. Use of a night light may be helpful.

- Maintain a low level of noise in the room and reduce negative distraction, e.g. loud television volume

- Place re-orientation cues, e.g. a clock, newspaper, daily schedules, familiar belongings such as photographs or other personal items

- Access to glasses or hearing aids (if required)

- Suggest relaxation or distraction techniques, e.g. gentle touch or massage, aromatherapy, music or radio

- Spiritual or religious guidance or support (if relevant)

Support the use of other complementary techniques or methods that the patient or their family/whānau want to try if they are unlikely to cause harm, e.g. traditional techniques such as Rongoā Māori, Ayurvedic or Chinese herbal medicines.

Initiate pharmacological treatment as indicated

If non-pharmacological interventions have been inadequate or if the patient is experiencing severe or distressing symptoms, e.g. hallucinations, significant agitation, pharmacological treatment can be initiated.1, 19

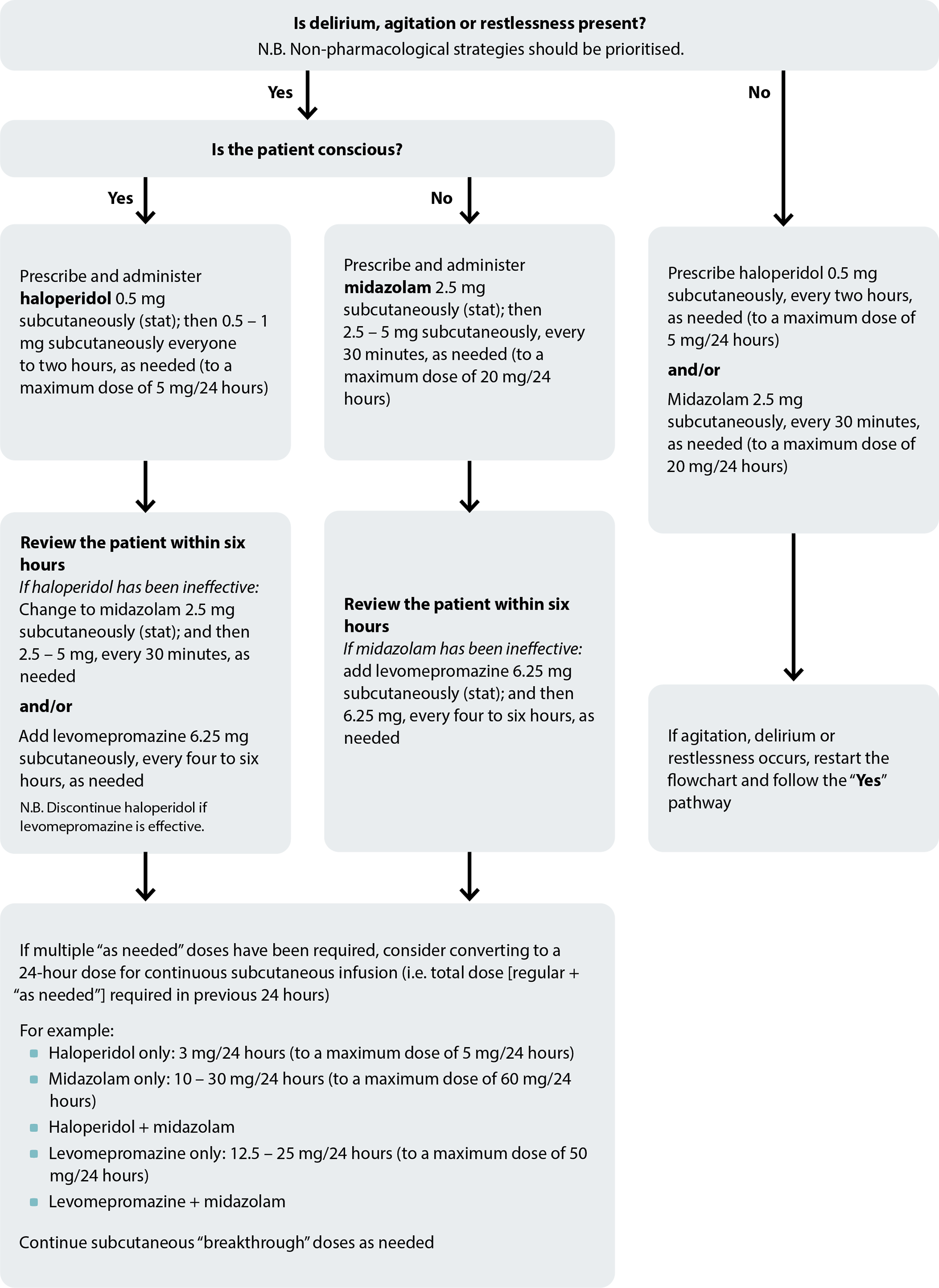

An antipsychotic (haloperidol) or benzodiazepine (midazolam) administered subcutaneously is recommended first-line for patients requiring pharmacological treatment for delirium, agitation or restlessness, with the initial choice dependent on consciousness level (Figure 1).6, 15 Benzodiazepines are particularly useful for patients with agitation and anxiety due to their sedating effects, but they can exacerbate symptoms of delirium at high doses.9, 10, 16 They are also useful for patients whose symptoms of delirium are caused by alcohol withdrawal.17 Haloperidol is particularly useful for patients who are also experiencing nausea and vomiting as it is the first-line treatment for this in the last days of life; combining indications means fewer medicines are required.

N.B. Some patients, e.g. those with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, will already be taking oral antipsychotics and require conversion to a subcutaneous formulation.15

Practice Point: Anticipatory prescribing of “as needed” subcutaneous doses of haloperidol and/or midazolam is also recommended in patients without symptoms of delirium or who do not yet require pharmacological treatment; if symptoms occur/worsen, the “as needed” dose can be administered and then regular dosing initiated (see regimens below).15

Practice Point: Anticipatory prescribing of “as needed” subcutaneous doses of haloperidol and/or midazolam is also recommended in patients without symptoms of delirium or who do not yet require pharmacological treatment; if symptoms occur/worsen, the “as needed” dose can be administered and then regular dosing initiated (see regimens below).15

Haloperidol is recommended first-line for patients who are conscious

If the patient is conscious or semi-conscious, 0.5 mg of subcutaneous haloperidol* should be prescribed and administered stat (subcutaneous injection; unapproved route),21 with additional doses prescribed on an “as needed” basis, e.g. 0.5 – 1 mg every one to two hours, as needed (to a maximum dose of 5 mg within 24 hours).15 Ideally, the patient should be reassessed within six hours of initiation to review treatment response.15

N.B. Antipsychotics can be associated with restlessness; consider haloperidol as a potential cause if a patient experiences worsening symptoms after treatment initiation.10, 18 Midazolam can be added early to reduce this effect (or used instead – see below), but do not persist with haloperidol if the patients’ distress is worsening.

If there has been inadequate response to treatment with haloperidol after six hours:15

- Switch to midazolam 2.5 mg, administered subcutaneously (stat), and prescribe additional “as needed” doses, e.g. 2.5 – 5 mg, every 30 minutes, as needed; and/or

- Add levomepromazine† 6.25 mg, administered subcutaneously, every four to six hours, as needed. Levomepromazine is a second-line option to haloperidol (with or without midazolam) and is highly sedative. If levomepromazine is used on an “as needed” basis with effect, discontinue haloperidol and convert the daily dose of levomepromazine to a 24-hour dose for continuous subcutaneous infusion, and prescribe additional “as needed” doses.

*Contraindicated in patients with Parkinson’s disease and should be avoided in patients with Lewy body dementia21

†Previously known as methotrimeprazine

Midazolam is recommended first-line for patients who are unconscious

If the patient is unconscious, 2.5 mg of subcutaneous midazolam (unapproved indication) should be prescribed and administered stat, with additional doses prescribed on an “as needed” basis, e.g. 2.5 – 5 mg, every 30 minutes, as needed (to a maximum dose of 20 mg within 24 hours).15 Ideally, the patient should be reassessed within six hours of initiation to review treatment response.15

If treatment is ineffective after six hours, add levomepromazine 6.25 mg administered subcutaneously (stat), and prescribe additional “as needed” doses, e.g. 6.25 mg, every four to six hours, as needed.15

Practice Point: Patients already established on high dose anxiolytics may require higher doses of midazolam.15

Practice Point: Patients already established on high dose anxiolytics may require higher doses of midazolam.15

Consider conversion to a continuous subcutaneous infusion

If multiple “as needed” doses of haloperidol, midazolam or levomepromazine have been required, consider converting to a 24-hour dose for continuous subcutaneous infusion, i.e. total (regular + “as needed”) subcutaneous doses required in previous 24 hours (Figure 1).15 Each of these medicines can be used alone for continuous subcutaneous infusion or combination treatment may also be trialled.15 Continue subcutaneous “breakthrough” doses as needed.15

Contact the local hospice or palliative care team for advice if the patient's symptoms do not respond to appropriate treatment, or if there is unwanted sedation.8

Contact the local hospice or palliative care team for advice if the patient's symptoms do not respond to appropriate treatment, or if there is unwanted sedation.8

Figure 1. Anticipatory prescribing flowchart for delirium, agitation and restlessness. Adapted from South Island Palliative Care Workstream, 2020.15

Support the patient’s mental health and wellbeing needs

Nā koutou i tangi, nā tātou katoa

When you cry, your tears are shed by us all

“Empathy has no script. There is no right way or wrong way to do it. It’s simply listening, holding space, withholding judgement, emotionally connecting, and communicating that incredibly healing message of ‘you’re not alone’” – Brené Brown

When caring for a patient experiencing psychological distress, the aim is for them, and their family/whānau, to feel comfortable explaining any fears or concerns.16 Use communication techniques such as asking open questions, active listening and the appropriate use of silences, speech tone and eye contact.16

Identifying the cause of the patient’s psychological distress in the last days of life is often difficult as there are usually multiple overlapping causes, such as:18, 22

- Fear of pain or other worsening symptoms

- Loss of independence or a sense of burden on carers

- Fear of dying

- Anticipatory grief

- Spirituality concerns

- Contemplating the meaning of life and their purpose

- Concerns about the needs of their family/whānau after they die

Managing psychological symptoms for patients in the last days of life

The initiation of conventional treatments for psychological symptoms, e.g. antidepressants or cognitive behavioural therapy for depression, is not appropriate in the last days of life as there is insufficient time to achieve any benefit, and patient participation will be limited due to fatigue or impaired communication.3, 18 Patients currently taking antidepressants for psychological symptoms should continue to do so until swallowing is no longer possible (if they are providing benefit).18

General supportive and non-pharmacological interventions are appropriate. Additional support may be required for patients with a pre-existing psychological condition.3 Non-pharmacological strategies may include relaxation or distraction techniques such as listening to music or watching television, aromatherapy, mindfulness-based techniques, reminiscing, spending time with family/whānau or a family pet or therapy animal.3, 15, 18 Ask about any coping strategies used in the past and whether these could be used again, if appropriate.7 Patients with spiritual distress may benefit from spiritual or religious guidance or support.3, 16

Some patients with insomnia, anxiety or depression may require pharmacological treatment with an antipsychotic or benzodiazepine administered subcutaneously, if conservative management is unsuccessful.3, 18 Opioid doses should not be increased to sedate the patient.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to the following experts for review of this article:

- Dr Kate Grundy, Palliative Medicine Physician, Clinical

Director of Palliative Care, Christchurch Hospital Palliative

Care Service and Clinical Lecturer, Christchurch School of

Medicine

- Vicki Telford, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Nurse Maude

Hospice Palliative Care Service, Christchurch

- Dr Helen Atkinson, General Practitioner and Medical

Officer, Harbour Hospice

- Dr Robert Odlin, General Practitioner, Orewa Medical

Centre

- Fraser Watson, Extended Care Paramedic Clinical Lead,

Hato Hone St John

N.B. Expert reviewers do not write the articles and are not responsible for the final content.

bpacnz retains editorial oversight of all content.

This resource is the subject of copyright which is owned by bpacnz.

You may access it, but you may not reproduce it or any part of it except in the limited situations described in the

terms of use on our website.

Article supported by Te Aho o Te Kahu, Cancer Control Agency.

References

- Azhar A, Hui D. Management of physical symptoms in patients with advanced cancer during the last weeks and days of life. Cancer Res Treat 2022;54:661–70. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2022.143

- PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. Last days of life (PDQ®): health professional version. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US) 2007 (updated 2023). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65868/ (Accessed September, 2023).

- Crawford GB, Dzierżanowski T, Hauser K, et al. Care of the adult cancer patient at the end of life: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. ESMO Open 2021;6:100225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100225

- Hosker CMG, Bennett MI. Delirium and agitation at the end of life. BMJ 2016;:i3085. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3085

- Sutherland M, Pyakurel A, Nolen AE, et al. Improving the management of terminal delirium at the end of life. Asia-Pac J Oncol Nurs 2020;7:389–95. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_29_20

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. Te Ara Whakapiri Toolkit: care in the last days of life. 2017. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/te-ara-whakapiri-toolkit-apr17.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- MacLeod R, Macfarlane S. The palliative care handbook-ninth edition. 2019. Available from: https://www.hospice.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Palliative-Care-Handbook.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Care of dying adults in the last days of life. 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng31 (Accessed September, 2023).

- Albert RH. End-of-life care: managing common symptoms. Am Fam Physician 2017;95:356–61.

- Mattison MLP. Delirium. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:ITC49–64. https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC202010060

- Agar MR. Delirium at the end of life. Age Ageing 2020;49:337–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz171

- Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2015;17:13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0550-8

- Shin J, Chang YJ, Park S-J, et al. Clinical practice guideline for care in the last days of life. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care 2020;23:103–13. https://doi.org/10.14475/kjhpc.2020.23.3.103

- Sanderson C. End-of-life symptoms. In: MacLeod RD, Van den Block L, eds. Textbook of Palliative Care. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2018. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31738-0_105-1

- South Island Palliative Care Workstream. Te Ara Whakapiri Symptom management in the last days of life. 2020. Available from: https://www.sialliance.health.nz/wp-content/uploads/Symptom-management-in-the-last-days-of-life_SIAPO.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Chapman L, Ellershaw J. Care in the last hours and days of life. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;48:52–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpmed.2019.10.006

- NHS Scotland. Scottish palliative care guidelines. Available from: https://www.palliativecareguidelines.scot.nhs.uk/guidelines.aspx (Accessed September, 2023).

- Crawford GB, Hauser KA, Jansen WI. Palliative care: end-of-life symptoms. In: Olver I, ed. The MASCC Textbook of Cancer Supportive Care and Survivorship. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2018. 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90990-5_5

- Clark K. Care at the very end-of-life: dying cancer patients and their chosen family’s needs. Cancers 2017;9:11. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers9020011

- Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7491

- New Zealand Formulary (NZF). NZF v135. 2023. Available from: https://nzf.org.nz (Accessed September, 2023).

- Ann-Yi S, Bruera E. Psychological aspects of care in cancer patients in the last weeks/days of life. Cancer Res Treat 2022;54:651–60. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2022.116