Vertigo and the vestibular system

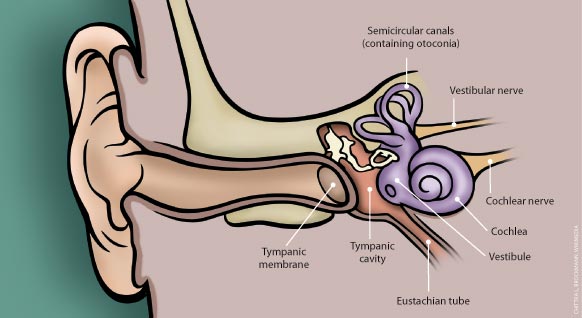

Our sense of orientation and balance depends on input from the visual and proprioceptive systems and the inner ear,

integrated in the brainstem vestibular nuclei and the cerebellum (Figure 1). In the inner ear, otolith organs in the vestibule

detect vertical and non-rotational movement (orientation in relation to gravity), and the ampullary receptors in the semicircular

canals detect rotation of the head. When the head rotates, the receptors on one side are stimulated and those on the opposite

side are inhibited. The eyes attempt to keep a visual fixation on the environment with quick movements in the opposite

direction, called the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR). At the same time, the vestibular nuclei send impulses to the limb

and trunk muscles to contract and preserve balance. Dysfunction of any of these structures can cause disorders of balance

and the sense of orientation, often leading to vertigo.

Figure 1: The inner ear

Vertigo is a symptom, not a diagnosis

Vertigo is a symptom, not a diagnosis. Peripheral vertigo arises from dysfunction of the vestibular labyrinth (semicircular

canals) or the vestibular nerve.1 Most patients presenting with vertigo in general practice have symptoms due

to peripheral causes, such as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), vestibular neuritis, Ménière's

disease or vestibular migraine (Table 1).2 A small number of people with vertigo will have a significant, serious

underlying condition, usually arising from a central cause such as stroke or a tumour, and will require urgent referral.

It is vital not to miss such cases, and wherever there is doubt, refer.

Table 1: Causes of vertigo (adapted from Kuo et al, 2008)

| Peripheral vertigo |

Central vertigo |

Other |

| Common |

Acute vestibular failure (vestibular neuritis)

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

Ménière's disease |

Vestibular migraine |

Psychogenic vertigo |

| Rare |

Cholesteatoma

Herpes zoster oticus

Labyrinthitis |

Cerebellopontine angle tumour (acoustic neuroma)

Transient ischaemic attack (brainstem or cerebellum)

Multiple sclerosis |

Medicines |

Key questions to consider in a patient presenting with vertigo

When a patient presents with vertigo, assessment can be based on the following three judgments:

- Are the symptoms being described most likely to be vertigo, dizziness or disequilibrium?

- If it is vertigo, is the cause suspected to be central, peripheral or other?

- Depending on the cause, what is the most appropriate management?

Is it vertigo or something else?

The first step should be to determine whether the patient's symptoms are due to vertigo, dizziness or disequilibrium.

Ask the patient to explain the sensation in detail.

Vertigo is a sensation of motion (usually whirling) either of the body or the environment, caused by

asymmetric dysfunction of the vestibular system.

Dizziness is a sense of spatial disorientation without a false sense of motion, often described as

light-headedness, generalised weakness and feeling faint. When intense, it is usually called presyncope. Presyncopal dizziness

usually has a cardiovascular cause and may be accompanied by other symptoms indicative of hypotension or anaemia, such

as pale skin or "clamminess". Common aetiologies include arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, hypovolaemia or orthostatic hypotension.3

Disequilibrium is a sense of being off-balance without dizziness or vertigo, particularly when walking.

The patient may describe feeling as though the floor is tilted or that they are floating. It can originate in the inner

ear or other sensory organs, from muscle and joint weakness or in the central nervous system. Disequilibrium is generally

caused by bilateral dysfunction of the vestibular system, rather than unilateral dysfunction as seen in vertigo. Causes

of disequilibrium include ototoxic loss of vestibular function, head trauma, cerebrovascular disease and progressive loss

of vestibular function due to age or spinocerebellar degeneration, osteoarthritis or multiple sclerosis.3

Patients with dizziness or disequilibrium may require further testing, and a serious underlying cardiovascular cause

or neurological disorder should always be considered. Further management of dizziness or disequilibrium is not covered

in this article.

What is the cause of the vertigo?

A history is important for defining the aetiology of vertigo

Once the patient's symptoms have been established as vertigo, specific features are used to help determine the cause.

The duration of each episode of vertigo is an important indication of the likely aetiology:1,4

- Seconds - likely to be psychogenic

- Less than one minute - likely to be BPPV

- Minutes - likely to be vascular/ischaemic

- Hours - likely to be Ménière's disease or vestibular migraine

- Hours to days - likely to be vestibular neuritis, central causes possible, e.g. stroke, vestibular migraine, multiple

sclerosis

- Recurrent with headaches, photophobia and phonophobia - likely to be vestibular migraine

The patient should be asked about specific factors associated with onset of the vertigo. The most important is head

position: is it triggered by lying down, rising, turning over in bed, looking up or stooping? Or does it start when they

are upright and still?

Is there a recent history of a head injury, even if trivial?

Are they taking any new medicines, such as regular aspirin or phenytoin?

Are there other symptoms associated with the vertigo such as tinnitus, hearing loss or aural fullness (pressure) in

one ear?

Are most episodes accompanied by headache? Is there a history of migraine?

An examination should help to confirm the cause

The examination should include:

Cardiovascular

- Heart rate and rhythm, with ECG if indicated by clinical findings: this is important for ruling out an underlying

cardiac cause for the symptoms

- Blood pressure, standing and supine (three minutes for each position) - a significant drop in blood pressure, e.g.

≥20 mmHg systolic, when moving from supine to standing suggests presyncope rather than vertigo

- Auscultation of the neck - the presence of a carotid bruit particularly if there are neurological abnormalities on

examination, may raise the suspicion of a central disorder, e.g. TIA or stroke

Red flags in vertigo diagnosis

Certain signs or symptoms indicate a possible serious underlying cause, for which the patient will require referral

to hospital. Red flags include:6

- Vertigo that continues for several days

- Nystagmus that is down-beating and continuing

- Unremitting headache and nausea

- Ataxia, cerebellar signs

- Progressive hearing loss

- Signs of suppurative labyrinthitis - bulging, erythematous tympanic membrane, fever, balance disturbance

Otoscopic examination of the ears

Relevant findings include are signs of inflammation, infection, secretion or malodour, and signs of cholesteotoma or

herpes zoster vesicles.

Best practice tip: When examining the ear with otoscopy, if there are any deposits

at the top of the ear drum, it is more likely to be a cholesteotoma than wax build-up.

Best practice tip: When examining the ear with otoscopy, if there are any deposits

at the top of the ear drum, it is more likely to be a cholesteotoma than wax build-up.

A focused neurologic examination

Initially, perform an assessment of the eyes, gait, balance and co-ordination and hearing. Further examination may

be required, depending on the clinical picture, to detect any neurological signs that may point towards a central cause,

e.g. motor or sensory changes in the face or upper limbs and tests of cerebellar function. If the vertigo is due to a

peripheral cause, there should be no abnormal neurological signs other than nystagmus (see "Defining nystagmus") and possibly

hearing loss.

- Examination of the eyes - e.g. presence of nystagmus, papilloedema

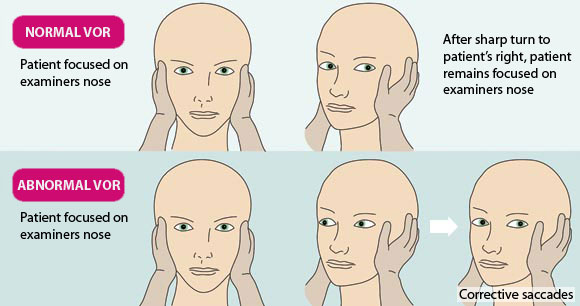

- Head impulse test - a test for the presence or absence of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) and a sign of unilateral

vestibular dysfunction (see "Head impulse test for VOR", below). An abnormal test significantly increases the likelihood

of a peripheral cause.

- Assessment of gait, balance and co-ordination - Romberg tests, heel-toe tests and cerebellar testing, e.g. disdiadochokinesia,

finger-nose tests. Poor balance or gait or cerebellar signs are significant red flags for a central cause.

- Basic initial hearing tests - N.B. a pure tone audiogram (to document fluctuating hearing in the affected ear) is

essential for a symptom-based diagnosis of Ménière's disease and may indicate the presence of an acoustic

neuroma. This will require referral for audiometry.

Specific positional testing

A Dix-Hallpike positional test (see "Performing a Dix-Hallpike test", below) is essential for all patients presenting

with, or with a history of, vertigo who do not have spontaneous nystagmus while upright.

Defining nystagmus

Nystagmus is the involuntary, rapid and repeated movement of the eyes. Nystagmus from a peripheral cause is usually

horizontal (across the eye) with a slow component to the symptomatic side (affected ear) and a fast component (VOR) to

the opposite side. The direction of the nystagmus is defined by the fast component, i.e. left, right, up or down-beating.

In general, nystagmus that fatigues with time, goes away with fixation (e.g. asking the patient to stare at your finger),

starts after a short delay and does not change direction with gaze is due to a peripheral cause. Vertical nystagmus is

usually a sign of an underlying central lesion. The upward torsional nystagmus of BPPV is the only exception.

Head Impulse Test for VOR

The Head Impulse Test is used to indicate the presence or absence of normal VOR.5 It is commonly used in

secondary care, but is a simple test that can also be carried out in the general practice setting. N.B. use with caution

in people with cervical spine disease. The patient should be asked to sit upright and to stare at the examiner's nose

without blinking. The examiner should turn the patient's head sharply and unpredictably to one side. The test is abnormal

if the eyes make corrective saccades (rapid movement of both eyes to maintain focus on a point) to re-fix on the examiner's

nose. This indicates a peripheral cause of the vertigo. In the illustration thrusting of the head to the right induces

corrective saccades.

Performing a Dix-Hallpike test

Adapted from BMJ Best Practice4

Adapted from BMJ Best Practice4

The Dix-Hallpike test is the diagnostic test for posterior canal BPPV. Before performing the test, warn the patient

that the test is likely to trigger vertigo or nausea. The test can be performed on an examination table or bed. Older

patients may find it easier to lie back with their shoulders on a pillow. The patient should be instructed to keep their

eyes open. While still upright, turn the patient's head 45 degrees to one side, then lie them back with their neck extended

over the head of the table/bed or pillow. A positive test must comprise a voluntary report of acute vertigo, and a delayed

up-beating (towards the forehead) and torsional nystagmus which is anticlockwise if the right ear is affected and clockwise

if the left ear is affected. The nystagmus should cease within 30 seconds. Sit the patient up.

Repeat the test on the opposite side. Ideally, test the suspected normal ear first and the suspected symptomatic ear

second. If there is no nystagmus it is not BPPV.

Based on the suspected cause, what is the most appropriate management?

Symptomatic treatments for benign vertigo

In many cases, patients can be reassured that their symptoms are not associated with a serious cause and are satisfied

to take a "wait and see" approach.

Antiemetics, e.g. prochlorperazine and cyclizine, are likely to be helpful to patients with spontaneous acute vertigo

with nausea. They are generally well tolerated, but are associated with adverse effects such as drowsiness, dry mouth

and blurred vision, so should be used with caution, particularly in elderly people. They should not be prescribed long-term.9

Benzodiazepines are not recommended, as they are likely to provide short-term symptomatic benefit, but they interfere

with the natural central compensation in vestibular conditions and prolong vertigo.10

Vertigo associated with a central disorder

The following features are indicative of a possible central cause:

- Recurrent or persistent vertigo

- Gait or movement abnormalities

- Constant nausea

- Poor performance on tests of cerebellar function, e.g. dysdiadochokinesis and heel-toe testing

Anyone with a suspected central disorder should be urgently referred to hospital. Common causes of central-disorder

vertigo include stroke, multiple sclerosis, vertebrobasilar ischaemia and tumours.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

A positive Dix-Hallpike test is diagnostic of posterior canal BPPV. Horizontal canal BPPV is a less common form which

can be seen as horizontal, direction-changing nystagmus as the patient's head is turned from side to side while supine.4

BPPV has a life-time prevalence of 2.4%, and most patients presenting to general practice with vertigo will have BPPV.3,6 BPPV

occurs when otoconia (Figure 1 above) in the vestibule of the inner ear become dislodged and enter

the semicircular canals, usually the posterior canal.7 In middle-aged and elderly people there is often no

obvious cause, but in younger people it is usually due to head trauma - even mild trauma may be sufficient to displace

otoconia.8 BPPV may also be secondary to vestibular neuritis.

Treatment: Perform an Epley canalith repositioning procedure (See "Epley canalith repositioning procedure" below).

The success rate for the Epley procedure is approximately 70% on the first attempt, and almost 100% on successive manoeuvres.8

When there is no response to repeated repositioning manoeuvres, or atypical or ongoing nystagmus or nausea is present,

a central cause should be suspected.7 When there is unusual horizontal or down-beating nystagmus referral to

an otolaryngologist is recommended.

Epley canalith repositioning procedure

This procedure can be performed in patients with BPPV. The goal of repositioning is to return the otoconia to their

original position on the utricle. The procedure is successful in approximately 70% of patients on the first attempt, and

approaches 100% effectiveness on successive manoeuvres. Repositioning is safe, but should be used with caution in people

with cervical spine disease, unstable cardiovascular disease, suspected vertebrobasilar disease and high-grade carotid

stenosis.

Tilt the patient back (neck extended over the end of the table/bed) with their head turned 45 degrees to the symptomatic

side (as in a Dix-Hallpike test) and hold them in that position for one minute. Then turn their head to the opposite side

at 45 degrees. Next, ask the patient to turn their hips and trunk (or assist them) until they are looking down at the

floor at 135 degrees (180 degrees from the initial Dix-Hallpike position), so that the upper section of the posterior

canal is vertical. After one minute ask the patient to sit up quickly with their head tilted toward the treated ear.

Older people may find it more comfortable to lie back over a pillow, rather than hanging their head over the end of

the table.

A repeat Dix-Hallpike test should be done and if there is no response, treatment has been successful. However, it cannot

be guaranteed that the repositioning has been successful. Younger patients can be instructed to test themselves at home

in two days by lying back over a cushion on the floor. Older patients should be asked to return and be retested.

If repeated repositioning procedures are unsuccessful or if there is unusual and continuing nystagmus and nausea, referral

is indicated.

Ménière's disease

Recurring episodes of vertigo, usually lasting for several hours, associated with fluctuating hearing, tinnitus and

aural fullness is suggestive of Ménière's disease, an incapacitating disorder of the inner ear.11 Ménière's

disease is caused by an excess of cochlear endolymph (endolymphatic hydrops) which eventually "refluxes" into the semicircular

canals to cause vertigo. As the vertigo episodes continue, hearing may decline to a "flat" sensorineural loss at 60 dB.11 Ménière's

disease usually occurs in people aged over 40 years, but in one-third of people it starts after age 60 years.12

Diagnosis: Patients with suspected Ménière's disease should be referred for further investigation

and confirmation of the diagnosis. Diagnosis is based on the classical symptoms and a pure tone audiogram test.11 A

MRI scan to exclude retrocochlear pathology is usually required. Some otolaryngology departments offer a specific electrophysiological

test for hydrops. N.B. Ménière's disease and vestibular migraine can be easily confused.

Treatment: Currently there is no treatment which can reverse the hydrops and the hearing loss. The

goal of management is symptom control.

The only oral medicine with some evidence of efficacy in controlling the vertigo episodes is betahistine.13 The

recommended maximum daily dose of betahistine is 48 mg/day (in divided doses), however, evidence suggests that significant

benefit is derived from doses greater than this.13 Diuretics have been used for Ménière's disease,

but are not recommended as there is a lack of evidence of benefit, and adverse effects are possible, particularly in older

people.14

Until recently, surgical treatment was the only alternative to pharmacological management.9 However, intratympanic

gentamicin is now being used by otolaryngologists.15 Diluted gentamicin is placed in the middle ear through

a myringotomy. The gentamicin is then absorbed into the inner ear. This does not treat the underlying pathology, but disables

the semicircular canal receptors causing the vertigo episodes. A single treatment usually results in cessation of vertigo

for several years.

Vestibular neuritis

A single, severe episode of vertigo, lasting at least 48 hours is suggestive of vestibular neuritis.16 The

principal signs are horizontal nystagmus and an abnormal head impulse test, which indicates a unilateral vestibulopathy.

If the head impulse test is normal, cerebellar infarction should be suspected. Vestibular neuritis is thought to be caused

by reactivation of the herpes simplex virus in the vestibular nerves.1

Treatment: Offer symptomatic treatment if required, e.g. if nausea is present, and consider referral

if symptoms do not resolve or if there is any doubt about the diagnosis.

BPPV may occasionally develop in the affected ear after vestibular neuritis, due to inflammatory disruption of otoconia.

Patients should be warned of the possibility of this complication and instructed to return for repositioning treatment

if they experience positional vertigo.

Labyrinthitis

Labyrinthitis is an older term which is often misused for vestibular neuritis. However, a patient with acute otitis

media who presents with vertigo, balance disturbance and hearing loss may have a viral or bacterial true labyrinthitis.17 IV

antibiotic treatment is usually required.9

Treatment: Refer to hospital.

Vestibular migraine

Recurrent, fluctuating vertigo that occurs with a throbbing headache, photophobia or transient visual symptoms is likely

to be migraine related.1 This occurs most frequently in people with a personal or family history of migraine.

Treatment: Treat as for migraine, if vertigo persists, reconsider the initial diagnosis (it is easily

confused with Ménière's disease) and consider referral to an otolaryngologist.

Medicine-related vertigo

Many recreational drugs, most commonly alcohol, can cause short-term vertigo. Prescribed medicines almost never cause

vertigo. However, many medicines, e.g. antihypertensives, can cause a fluctuating disequilibrium and this cause should

always be considered.

Treatment: Trial cessation of the suspected medicine where possible.

Follow-up is essential for all people with vertigo

Continuing or worsening symptoms in people with vertigo may indicate an incorrect initial diagnosis or the possibility

of a serious aetiology. Patients with vertigo should be instructed to return if their symptoms persist unexpectedly.

After otolaryngological diagnosis of a persisting and non-fluctuating peripheral vestibular disorder, vestibular rehabilitation

may be beneficial.18 This is a movement and exercise-based treatment offered in hospital physiotherapy departments

and in some private clinics.